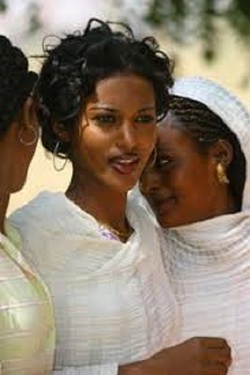

International Women’s Day affords an opportunity to consider why FGM has become such an important issue worldwide and a major one in Britain. Here, I explore the problematic, even anti-humanist efforts being made and promoted in trying to ‘eradicate‘ it, the implications for what the state, campaigners, feminists and charities are doing, the consequences for affected communities and professionals, followed by some recommendations. Why does FGM have such a resonance? This is probably due to a coincidence of interests which include: Politicians of all persuasions, looking for an issue around which to galvanise popular support, were willing to believe that there is a big problem in regard to violence against women and girls (VAWG) generally, and among ‘hard-to-reach’ immigrant communities in particular. They became keen to be seen to be doing something about this nationally and internationally. FGM = VAWG. Articulate and imaginative survivors, activists and campaigners, some proudly calling themselves ‘feminists’, were pleased to gain a much sought after hearing, to front independent initiatives and/or get involved in Government led ones. They, understandably, wanted an end to this ‘barbaric’ and ‘mutilating’ practice. It is perceived a human rights violation that bodes no challenge. There is a widespread belief that children are uniquely vulnerable, that child abuse is rife in Britain, that FGM is child abuse and any form seen represents just the ‘tip of the iceberg’. Some NHS workers, midwives in particular, were seeing more pregnant women who had undergone FGM before arriving in the UK, and were trying to get additional resources to support and care for them. More asylum claims were being made by women fearing FGM for themselves or their children. The issue became a priority despite that there was no concrete evidence of FGM being practiced here, or of children/young women being taken abroad during the so called ‘cutting season‘. Nobody had an idea as to the extent of the problem but all seemed certain there was a big one. Campaigners therefore got an unprecedented hearing. City University/UNICEF/WHO data informed initial and continuing perceptions of incidence, here and overseas, but these are not factual. They represent instead predictions, estimates, even guesstimates which take insufficient account of changes in the prevalence and extent of the practice. These have mostly been wrought independently in the UK. Even when updated, prejudicial estimates of girls ‘at risk’ are cited and continue to be quoted almost as fact. New eye-catching headlines like ‘One Every 96 Minutes’ for example are based on non-comparable HSCIC data. We still have little idea of the numbers of women living in Britain who’ve undergone FGM or of the types, but it is always portrayed as ‘tip of the iceberg‘. In the public mind, most women and girls are considered to have undergone infibulation, which is highly unlikely. The UK Home Affairs Committee enquiry appeared willing to believe witness anecdotes, estimates and predictions as fact and made recommendations based on these, some of which have now been implemented. A Doctor accused by the Crown Prosecution Service of re-infibulating a woman post-delivery, underwent a politically expedient prosecution. He fortunately was not convicted by a jury. This generated huge media attention to the detriment of his career. The police, ever keen to secure a conviction, are convinced there’s still a hidden but unreported FGM problem. The Girl Summit gave the British Prime Minister a platform to show the world how much Britain cared about VAWG/FGM, supported by many charities, activists and campaigners. State machinery has been constructed around the issue, led by an enthusiastic team at the Home Office FGM Unit. Lead clinicians like midwives have been co-opted to support the work but have lost what independent or critical voice they may have had in furthering the aims of the FGM crusade. National roadshows ‘raised awareness’ and ‘educated’ professionals. These sowed the seed that FGM was a new form of child abuse that all were missing and needed to become more vigilant in regard to. FGM subsequently became ‘everybody’s business’. Professionals and ‘survivors’ were told that women who had undergone FGM would have health, psychological and sexual problems, hence the need for more funding for specialist services like therapy, community engagement and education. Some victims/survivors ‘went public’, telling their stories, often in graphic detail. Some disagreed and reported it wasn’t the problem, as presented, for them. Pester power became influential through teenagers recruited from traditionally practising communities. They pressured the then Education Secretary into writing to School Heads, telling them they must discuss FGM with staff and school children. NHS prevalence data was collected and was problematic from the outset. But because it generated welcome media attention for the Department of Health, it re-confirmed for the Government that the problem it needed to address was huge and worthwhile. The new NHS enhanced dataset is inaccurate as well as unpopular and few centres are reporting. The actual number of centres expected to report remains unclear. Although there are approximately 8076 GP practices and 212 Acute and Mental Health Trusts, not all would be expected to see affected women and girls to report. The dataset remains unpopular with some clinicians and FGM reporting is a hot topic for Caldecott Guardians. The need for more FGM laws was popularised but not challenged. The new FGM Protection Orders have created major problems, resulting in police involvement in families, court appearances, passport removals, travel restrictions, airport surveillance, visas denied, fares lost etc. Mandatory Reporting is based on the premise that FGM is an exceptional form of child abuse and unlike any other. It demands of registered professionals that they report FGM in U18’s direct to the Police. Knowing this, some young women are avoiding health care professionals, fearing the consequences.  Few, if anybody, is seeing young women who’ve been cut in Britain. Even the clinicians at the specialist national centre for under 18’s at UCLH in London, have seen a maximum of 27 girls who may have undergone type IV FGM, somewhere. Just three cases are being investigated by the police. Even the experts there find it impossible to confidently distinguish this minor form from the tiny vulvar irregularities that may exist due to congenital variation. Exploratory studies are showing trends of radical change in the practice within western migrant communities, especially of the most extensive form. But if only one child is saved, feminists, politicians, the Department of Health, professional bodies etc. believe it is all worthwhile. Anti-FGM campaigns have become an anti-humanist, moral crusade. How do communities feel? The focus in Britain is mostly on Somali people, and to a lesser extent on Sudanese, Ethiopians and Eritreans. Egypt is mostly referred to because of the medicalisation of the practice there. West African countries get discussed mainly in regard to efforts being made to have the practice banned. When other parts of the world where FGM may be practised are newly identified e.g. Iraq, Indonesia, Gujarat, campaigners get very excited. While some women living with problematic symptoms have been helped and many health professionals have learnt about the prevalence and types of the practice, better and more sensitive care is hopefully being offered. But this is being offset by the surveillance and constant questioning that people under suspicion have to endure. The assumption that if mothers have undergone FGM, they will in turn have their daughters cut, is hugely problematic and hurtful. And that older women in Britain are being viewed as a particular threat because they put the younger women under undue pressure to conform, contradicts reality. So called ‘practising communities’ here, particularly Muslims, feel shamed, hurt, disappointed, stigmatised, even under siege. Across the country they say they independently stopped cutting girls when they understood that it was not demanded by their religion. But they’ve had little acknowledgement of these efforts. Or credit for having made them. Girls/young women who’ve been cut in their country of origin continue to come to the UK and their communities are keen to see them get the help and support they need. Some may have associated problems. Some may not. Many men are hurt by the accusations that they willingly benefit from women and girls undergoing the practice despite their suffering and the consequences. This is simplistically based on the assumption that it’s due to ‘patriarchy incarnate’. The trust that women have in health professionals, midwives and GP’s in particular, is being severely tested and for some, actively undermined. This is worsened by professionals seemingly too close collaboration with Social Care and the Police. Many immigrants prefer not to have contact with those services and fear their involvement. Some women dislike having Social Care staff involvement in ante-natal consultations with midwives, but fear saying so.Women are constantly being asked by health professionals whether they’ve been cut and if so, whether they intend cutting their daughters. They feel upset by this but are mostly unconfident about objecting. Some who understand that their personal details are being centralised to the HSIC are unhappy about it. And are confused by the associated consent/non-consent aspects. Women do not all agree that they will experience psychological problems from being cut. Even women who’ve undergone a ‘Type III’ (infibulation) say life goes on and that they have more important things to worry about. Some say they prefer the aesthetic result of an infibulation because that’s what is normal for them. A few adults would like to be re-infibulated post delivery, but can’t because it’s illegal. They find this lack of choice, as adults, incomprehensible. Some women would like to be able to explore the possibility of reconstructive surgery but there’s no NHS provision for this. Women who want it done have to go elsewhere. Mothers don’t like sensitive and private information, like their FGM status, being recorded in their child’s health ‘Red Book’ for others, including their children, to see. The focus on FGM could promote divisions between children, their parents and extended family when children e.g. bring home information from school about FGM (reverse socialisation). Neither do they welcome the promotion of the need for ‘safe houses’, as though parents pose a threat to their children. Some parents do not want FGM made a component of the school’s PSHE education curriculum or to become part of sex and relationship education. Because FGM remains a very private topic, communities in Britain do not yet speak publicly about it. So official hype and misinformation remain unchallenged. And though they feel bad about this, few feel able to summon the courage to correct it publicly. None of the 17 mandatory reporting referrals to the Police to date have been about young women born in the UK. The impact of these unnecessary police investigations, on those families, needs to be considered. Fewer than 40 FGM Protection Orders have been issued by the Courts. Some of these will have been to families with 1-4 children. Some families dispute the need for those issued. Word of mouth ensures that details of these referrals and investigations get reported within and among communities, increasing their suspicion and wariness of professionals and officials. FGM has become a popular topic for Masters and PhD students but communities, while generally willing to co-operate, think this may reflect a purient development in society when they have so many other and far more important issues that concern them. How do professionals feel? Many voice private concerns about the ‘FGM agenda’ but think they’re alone in having them. Some realise how much authority they have as professionals and how much damage they can cause simply by ‘raising concerns’. So they worry about this, but fear the consequences of not. Child protection is high on agencies’ agendas. But many understand, while not condoning it, that FGM is not classical ‘child abuse’. The intent is not to hurt but to protect girls/young women in ways that families consider best. Neither is it a repetitive act of violence. The context needs to be considered. We’re constantly being told that FGM is a prevalent but hidden practice so need to be suspicious of ‘practising’ immigrant communities, and on the alert for potential signs and symptoms in children. Few health professionals e.g. have encountered girls who’ve been cut, but because of what the Department of Health and others say, consider it widespread nevertheless. Professionals have been led to believe that nearly every woman who’s been cut will experience problems. But not all will. So much will depend on the type they’ve undergone and how much they perceive it of importance to them. Neither will they necessarily all suffer psychological damage. But if they keep being told they will, they are surely more likely to? However, when women need psychological support there is still little available to them. Health professionals’ concerns Obstetric and Gynaecology doctors are acutely conscious of what happened to theirprosecuted colleague, thinking ‘there but for the grace of God…’. Fewer are consequently considering careers in these specialities. Regulated professionals do not want to become what some term ‘police snitchers’ throughMandatoryReporting requirements. When experts find it impossible to confidently distinguish ‘Type IV’ from the tiny irregularities that may exist due to congenital variation in children, it begs the question as to the accuracy of what little data there is about FGM in U18s and generally. Social Care concerns Social Care workers sometimes get FGM referrals they don’t even know what to do with – because nothing needs doing. But because they’ve been made by e.g health professionals, some feel they must ‘investigate’. Some nursery workers are unhappy with being encouraged to monitor covertly, to e.g. inspect children’s genitals while changing nappies. They dislike the climate of suspicion that’s being promoted based on a presumption that children are being subjected to FGM at a younger age because parents are ‘becoming wise to the fact that professionals are now more aware of the issue.’ Educational concerns Some do not want FGM to become a key component of the school’s PSHE curriculum. Teachers don’t like having to be suspicious of families’ reasons for wanting to take children abroad for extended periods, even during school holidays. Teachers have reported young schoolgirls as possible FGM victims. That they were later diagnosed with e.g. anal itching from thread worms, period pains, discomfort from a bony injury etc. has been discomforting and an embarrassment for all concerned. Police concerns The police remain keen to secure a conviction and want to work closely with other key professionals: to encourage the referrals they believe are not being made. There is anecdotal evidence that FGM Protection Orders are being sought despite any intent by families to have girls cut, but issued solely on the basis of professionals’ suspicion. That the 17 young people referred through Mandatory Reporting were found not to have been cut in Britain, won’t make reporting professionals feel any better about having to work ‘in partnership’ with the Police. Border Agency concerns Suspicion is being transmitted through the service about travellers to specific parts of the world, or of those taking a supposed non-conventional route to their destination. And about an (imagined) emerging trend of ‘cutters’ being imported. Passengers do not welcome being viewed with suspicion and being met and screened coming off planes from ‘high risk’ areas even if the staff are sometimes the sensitive ‘Gatwick Angels’. What next? The anti-humanist, FGM moral crusade is an edifice built on sand and the scaffolding needs to be dismantled before it crushes more of the people it is meant to be helping. FGM is a complex issue and one we would all like to see an end to, but through conviction, not fear. It has however been turned into a simplistic, good or bad, right or wrong cause here. We are told what Britain is doing to ‘eradicate FGM is being lauded as exemplary in Europe and this is worrying, considering the problems outlined above. There is a need to challenge the misinformation, outlook and orientation using as many opportunities and fora as possible. It’s unlikely that FGM is being carried out in Britain. Recent research confirms that radical change is well underway in regard to the practice across Europe. Neither is there evidence that FGM is happening in Britain, and what official data there is, confirms this. So why the need for the constant ‘awareness raising’, the high profile campaigns and interventions? There are of course women/young girls living in Britain who have undergone FGM. Some may have been cut here in the past, most however will have been cut elsewhere. Whichever, they need to be treated with respect and have access to whatever expert care they may need throughout their lives. A girl/woman who underwent FGM in her or her family’s country of origin as a child, should be of no interest to the police, social care or even healthcare professionals except where it impacts negatively on her health. The FGM laws should be repealed and there should be no need for police involvement unless a crime has been committed. Many campaigners, feminists, project leaders, service staff and individuals have become almost evangelical in their approach to the issue. They seem to believe they are saving girls from a fate worse than death, so almost anything goes. Some are amazed that anybody might want to question their tactics or approach. They are also very sensitive to being challenged and some actively oppose attempts to engage. But do we all have to sing from the same hymn sheet? The Department of Health ignores concerns about the ethical issues raised in regard to Patient Identifiable Data collection and centralisation, the associated double standards in health care provision, the fears expressed about a slippery slope, etc. Accurate data still needs to be collected about FGM – like it is about other conditions. This should not be challenging for modern NHS systems. A lot of people, organisations, campaigners, pressure groups, charities etc. are actively working to keep the issue ‘alive’, and argue, despite proof, that it’s still happening in the UK. On this basis, they apply for funding for ever increasing interventions, education, community outreach, engagement and involvement. Others claim the frontline services needed are still not being funded or provided. If, in a few years time, when there’s still no evidence of FGM being practised here, the Government, its departments, feminists and campaigners will no doubt claim credit for its ‘eradication’ because of the work they’ve done through the high profile campaigns, the enactment of laws and their general zeal and commitment to the cause. And they’ll get away with it unless challenged, now. Some women who have undergone FGM face particular problems. How we help demands a more humanist approach than they have experienced of late and as was alluded to here by the women who do not identify as feminists on International Women’s Day.  ABOUT THE AUTHOR - BRÍD HEHIR Bríd is a retired health professional. She started her career as a (volunteer) nurse and midwife in Africa, in Ethiopia and Botswana, where she worked for almost four years. She encountered FGM/C in Ethiopia. She then moved to London where she worked in the National Health Service as a midwife, community nurse, health visitor, reproductive and sexual health nurse and manager over a period of 30 years. She did not encounter FGM/C during that time despite working with immigrant communities who are reported to practice it still. She is puzzled by the current reported prevalence of the practice, the official response and associated activism. And is worried that they might cause more harm than good.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed