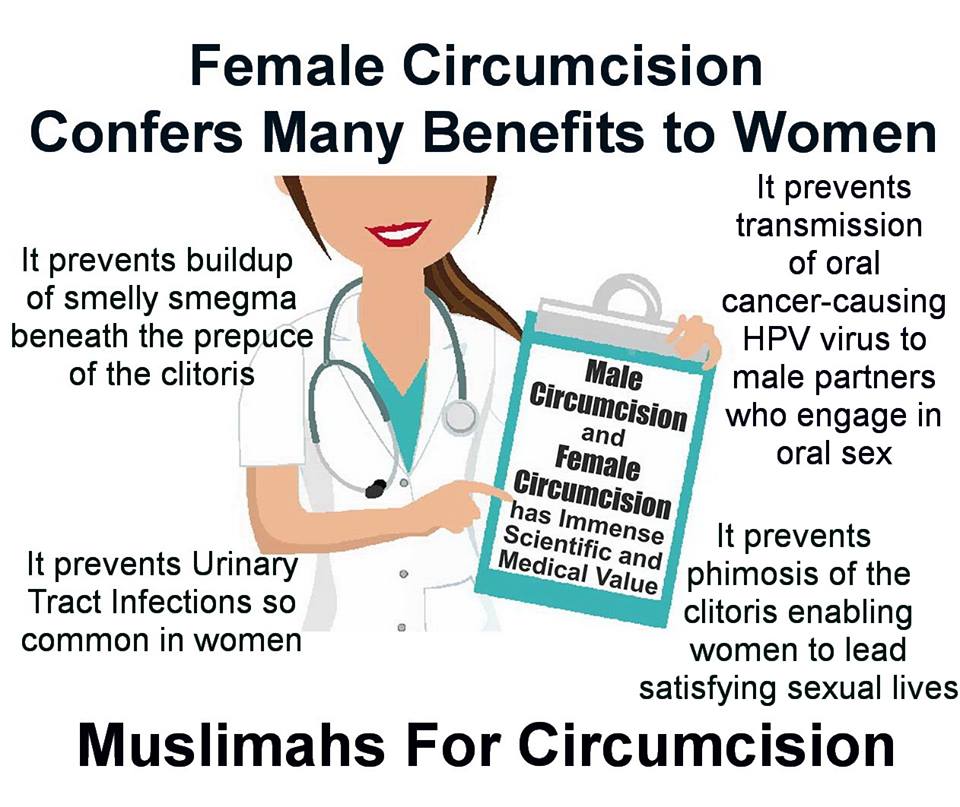

by Denise Noe for SiA MagazineFemale circumcision, like male circumcision, is common in Singapore. As is true elsewhere, controversy centers on that of females. As also true elsewhere, those who support the practice or take no position on it often use more benign sounding terms like Female Circumcision or Female Genital Cutting while opponents use Female Genital Mutilation or FGM. The city-state of Singapore is perhaps best know for its harsh punishments including the 1994 caning of American teenager Michael Fay for vandalizing cars, the 2005 execution of an Australian for drug smuggling, and the 2007 executions of two Africans for drug smuggling. One of Asia's economic tigers, Singapore has astounded the world with its robust economy, population density coupled with successful population control program, and strict laws. Over 75% of Singaporeans are Chinese, with Malays the second largest ethnic group and Indians third. Great Britain colonized Singapore in 1826, however in 1942 during World War II, Singapore fell briefly to Japan and then returned under British rule with Japan’s defeat in 1945. The Government is made up of a largely ceremonial president, a ruling prime minister, and a one-house parliament. Lee Kuan Yew become first prime minister of an independent Singapore in 1959. Lee Kuan Yew's son, Lee Hsien Loong has been in office since August 2004. Halimah Yacob made history in 2017 when she became Singapore’s first female president. Singapore has no laws regarding female circumcision.Female circumcision occurs primarily among Singapore’s Malay Muslims and is called “sunat perempuan.” Sunat comes under the World Health Organization (WHO) FGM/C classification of Type I. The Type I practice among Singaporean varies: a sharp instrument symbolically placed with no actual cutting, a nick to the clitoral hood, clitoral hood removal, or a small cut to the clitoral glans. In Singapore today, female circumcision is usually performed in medical clinics by doctors rather than in homes by midwives as in the past. The procedures typically are done on small children. According to The Asian Parent Singapore, “Some clinics even offer a package deal, if done in conjunction with ear-piercing.” A Southeast Asia Globe article estimates that four in five of Singapore’s 200,000 female Muslim Malays have been circumcised. Anti-Female Circumcision activist Saza Faradilla believes that 60% of Malay women in Singapore are circumcised. Why do Singaporeans practice FC? As with most supporters of female circumcision in Southeast Asia, Singaporeans interviewed tend to cite three reasons: hygiene, chastity, and religious practice. Some believe sunat, like male circumcision, helps hygiene. Saza writes, “They believe a part of the vagina traps dirt and needs to be removed, which makes for easier cleaning.” However, some counter that the mildness of female circumcision in Singapore means it cannot facilitate hygiene because, as Saza writes, the “cut is so small, it doesn’t affect anything. According to some Malays in Singapore, female circumcision “prevents unpleasant odors which result from foul secretions beneath the prepuce, reduces the incidence of urinary tract infections, and reduces the incidence of infections of the reproductive system.” According to a BBC report, “Many Malay Muslims, especially amongst the older generations, believe the procedure reduces a woman’s libido and decreases the risk of extramarital sexual affairs." Of course, this reason causes consternation among those fearing female circumcision is female castration. For some, believing it is Islamic means there is no need for practical purposes. The Asian Parent Singapore interviewed a Singaporean circumcised woman who said, “It’s for religious reasons.” That woman recalled that her circumcision hurt “just a tiny bit, like an ant bite. I was fine within five minutes.” Singapore has Muslims who dispute that sunat is religously compulsory. Dr. Maznah Mohamad, teacher in the Department of Malay Studies at the National University of Singapore, asserts, “If performed, one gets extra merit but if not performed, it is not considered sinful or going against the precepts of Islam.” The Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) is an advisory board holding much moral authority. Its website once stated “circumcision is compulsory for men and women.” The statement was dropped a few years ago. More recently, MUIS stated that “from the religious perspective” it “does not condone any procedure that brings any harm to the individual.” It “advises that female circumcision should only be performed by medical professionals, who will first assess if the procedure is harmful to the client and if she is suitable to undergo the procedure, before carrying out the procedure safely.” The group further states, “Where harm to the individual can be established in a procedure, it would be prohibited under Islamic law.” MUIS appears to equivocate, neither condemning nor supporting. There are Singaporeans campaigning to end sunat. Among them is the women’s organization Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE). However, AWARE spokesperson Filzah Sumartono says it is premature to suggest Singapore outlaw it. Interviewed by Reuters, Sumartono said, “In my own circle of friends who are Malay and Muslim, 100% have been cut. But it is very hidden. Whenever I bring up the subject with non-Malay they’re shocked and can’t believe it happens in Singapore.” After acknowledging that Singaporean female circumcision is relatively mild, she continued, “At its foundation, it is really an act of violence against women. At infancy already, the child is taught that your body is not your own.” Like so many who discuss this issue, she made no comment about what circumcision teaches boys. A spokesperson for the Britain-based Orchid Project, an organization seeking to stop female circumcision, asserts that even mild forms of female genital cutting “is a human rights issue.” She continues that it is “most often carried out to control and suppress female sexuality, and the increasing medicalization of cutting in countries such as Singapore legitimizes a discriminatory practice that both underpins and reinforces gender equality.” The Orchid Project finds the “middle-of-the-road” position of MUIS unsatisfactory, a spokesperson pointing out that their statement suggests female circumcision “can be carried out ‘safely’” while the Orchid Project insists it is “a form of violence against girls and women” and “inherently harmful.” Saza recalled going to her cousin Anisah’s second birthday celebration. A college sophomore at the time, Saza learned that female circumcision had been performed on Anisah the week before. Saza asked, “Women need to be cut?” Told “yes,” Saza called it a “human rights violation,” and was informed, “You were cut, too.” Shocked, she researched the practice while attending Singapore’s Yale National University of Singapore and wrote her thesis on female circumcision. She started campaigning against it. Indeed, Saza staged a creative performance art demonstration at Yale-NUS in which she appeared wearing a skirt made up of parental consent forms reading “I agree with my child undergoing female circumcision.” She also wore what Southeast Asia Globe described as “an intentionally too-tight, bright-red” top intended “to highlight her discomfort in her own skin – and bring to mind the richness of blood.” Saza set out a box filled with scissors, inviting people to cut skirt and blouse. Interestingly, there is at least one Singaporean organization opposing female and male circumcision. It is “Crit Talk,” co-founded by Nurulsyahirah “Sya” Taha. “At Crit Talk, we address FGC together with male circumcision in the context of performing medical procedures on children without medical necessity and without informed consent,” Sya explains.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed